Food allergies significantly affect families’ quality of life. Why are food allergies on the rise? Four theories could explain why this is the case: the hygiene hypothesis, trends towards delayed allergen feeding, exposure to allergens through the skin, and not enough Vitamin D exposure. Learn about all of these theories here.

1 in 13 children has a food allergy – and food allergies are on the rise in both children and adults. In particular, the rates of peanut allergies have more than tripled in recent years.

When someone has a food allergy, eating even a small amount of food that they’re allergic to causes their immune system to overreact, because their immune system mistakes that food for a harmful invader. This causes their body to develop symptoms of an allergic reaction. And any allergic reaction could become severe – or even life-threatening.

Food allergies have a significant effect on quality of life. Children and adults with food allergies often can’t enjoy the same foods as friends and family. They must be extremely careful when eating at restaurants – and almost anywhere outside of their own home – because of the risk of cross-contact with their allergens. And many young people with food allergies are excluded or bullied, all because of their allergies.

But people aren’t born with food allergies – rather, these allergies develop over time. And food allergies develop due to a combination of genes and environmental factors.

Why are food allergies on the rise? It’s likely due to a combination of factors, not just one. And scientists are still investigating the possible reasons behind this increase.

There are many theories that could explain the rise in food allergies. Today, we’ll dive into four of these theories. It’s important to note that they all deal with the rise of food allergies in children, not adults.

The hygiene hypothesis

According to the hygiene hypothesis, the more exposure that someone has to common germs and infections, the less likely they are to develop a food allergy. But if they aren’t exposed to common infections, bacteria, and microbes, their immune system may start to believe that benign food proteins are harmful invaders, and over-react to them. After all, their immune system didn’t have to fight against many viruses and bad bacteria, which pose a legitimate threat to the body.

Thus, the less exposure a child has to germs, and the more hygienic their family's home and environment are overall, the more likely they may be to develop a food allergy. And several studies support this hygiene hypothesis.

One study’s results, for instance, showed that children with siblings, and children in daycare or childcare settings, were less likely to develop allergies. The more peers a child was around, in other words, and the more illnesses and infections they were exposed to, the lower their allergy risk was.

Another angle of the hygiene hypothesis involves the fact that not all bacteria are bad. There are many microorganisms that are harmless, and that may even help the immune system out. Some scientists call these microorganisms and microbes “the old friends.” The hygiene hypothesis poses the theory that, if someone spends most of their time in sanitized spaces, and not enough time out in nature, they aren’t as exposed to the “old friends” that may keep their immune system from overreacting.

The hygiene hypothesis may explain why wealthier countries (with cleaner overall hygiene conditions) tend to see higher food allergy rates, and why people in cities are more susceptible to allergies than people who live out in the country. But it still doesn’t seem to cover the whole picture of the rise in food allergies.

Delayed allergen feeding trends

Starting around 30 years ago, and continuing until relatively recently, people thought that delaying the feeding of common allergens for 1-3 years was the best approach. But this wasn’t backed by science. When recommendations to delay allergen feeding were introduced, they weren’t supported by any studies. Instead, they were just based on guesses from doctors.

Now, though, three landmark clinical studies on when to introduce common allergens have turned this thinking on its head.

These recent studies – the LEAP, EAT, and PETIT studies – show that babies should be consistently introduced to allergens within their first year of life, and parents should not delay allergen feeding.

In all of these studies, babies were randomly assigned to either eat common allergens starting around 4 months of age, or completely avoid all foods containing those allergens for a set period of time:

LEAP Trial (Learning Early About Peanut Allergy)

- Included 600 babies, all 4-11 months old

- All had a higher risk for peanut allergy

- Were randomly assigned to eat peanut regularly (at least 3 times a week) until age 5 or avoid peanut completely until age 5

EAT (Enquiring About Tolerance) Trial

- Included 1,300 babies, all 3 months old

- None had a higher risk for food allergies

- Were randomly assigned to eat six different foods (peanut, egg, milk, sesame, whitefish, wheat) regularly for 3-6 months, or completely avoid all of those foods for at least 6 months

PETIT (Two-step egg introduction for prevention of egg allergy in high-risk infants with eczema) Trial

- Included 147 babies, all 4-5 months old, participated

- All had a higher risk for egg allergy

- Were randomly assigned to eat egg daily, or avoid egg completely, for 6 months

All three of these studies’ results showed that early allergen introduction – consuming the foods early and consistently – led to healthier outcomes for children later in life. But in the groups where allergen feeding was delayed, children were much more likely to develop allergies to those foods.

These studies have led to new medical guidelines for introducing allergens, including guidelines from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI). The AAAAI guidelines state that, “to prevent peanut and/or egg allergy, peanut and egg should be introduced around 6 months of life, but not before 4 months.” They also recommend that “other allergens should be introduced around [4-6 months of age], and that parents and caregivers should “not deliberately delay the introduction of other potentially allergenic... foods.”

Interestingly, a significant spike in peanut allergies in the 1990s and early 2000s also aligns with the timeframe where people started to think delaying allergens was best.

According to Dr. Jonathan Spergel (Head of Allergy at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia), around the 1960s, infants would begin eating peanut-containing foods when they were only a few months old. At that time, food allergy prevalence was very low. But around the 1990s, when doctors started recommending delayed peanut feeding, peanut allergy rates started rising significantly.

Skin exposure

Another emerging theory poses that exposure to common allergens through the skin leads to very different outcomes, compared to eating the allergens. While eating common allergens at the right time may reduce a child’s food allergy risk, too much exposure to these allergens via contact with the skin may make a child more likely to develop a food allergy. This is known as the dual allergen exposure hypothesis.

The dual allergen exposure hypothesis may be part of the reason why babies with eczema have a sharply increased risk of developing a food allergy.

Babies with eczema have a weak skin barrier. This compromised skin barrier makes it a lot easier for irritants – and common food allergens – to pass through. When eczema babies' skin comes in contact with proteins from common allergen foods, like milk in a lotion or thinned peanut butter splatters on a high chair, their damaged skin barrier easily lets these proteins through. So, they often end up with more skin-based exposure to allergens than babies without eczema do.

Not enough Vitamin D exposure

Both the sun and foods supply Vitamin D, which is an important vitamin for immune system function. Although this theory isn’t as well-investigated as the three other theories above, one theory notes that food allergy rates have risen as a population gets less exposure to Vitamin D.

Countries with a higher average amount of time spent indoors – and less average time in the sun – have higher food allergy rates. And people in countries near the equator (where they get the most sun exposure) have the lowest food allergy rates, with allergy rates increasing the further away you get from the equator. Although this theory still needs a lot more research, it may indicate that sun exposure and eating Vitamin D-rich foods could possibly make a difference in whether your child develops a food allergy.

Pros And Cons Of Sippy Cups

Thinking about giving your little one a sippy cup? Today, we’ll co...

What Toddlers Eat In A Day: 12-18 Months Old

Looking for ideas of what to feed your 12-18 month old little one? ...

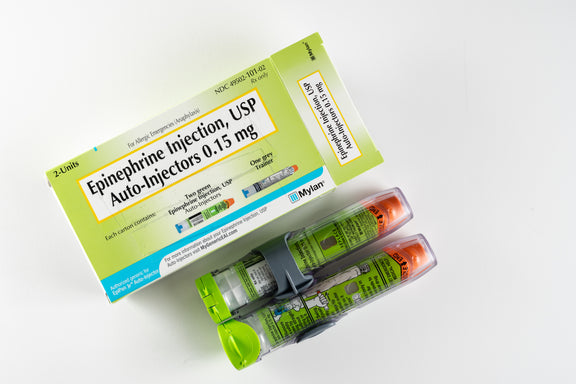

New Study Shows That Infant Anaphylaxis Usually Resolves With One Epinephrine Dose

A recent study has shown that, when infants experience severe aller...

Pregnancy Nutrition: What To Eat In The First Trimester

What to eat in the first trimester that will nourish your body, pro...

Formula Feeding Amounts: How Much Formula Should You Feed Baby Per Day?

How much formula should baby drink per day? It depends on their age...

What Baby Eats In A Day: 6-12 Months Old

Looking for ideas of what to feed your 6-12 month old little one? H...

All health-related content on this website is for informational purposes only and does not create a doctor-patient relationship. Always seek the advice of your own pediatrician in connection with any questions regarding your baby’s health.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease. If your infant has severe eczema, check with your infant’s healthcare provider before feeding foods containing ground peanuts.